I made it! It's May 31st, the end of the Blogathon. I've learnt a lot, discovered some lovely new blogs to follow and had fun along the way. I hope you've also enjoyed reading my children's books in translation series, and here's one more recommendation to round it off...

I was unexpectedly thrilled when browsing through the Outside In World website to rediscover Fattypuffs and Thinifers by André Maurois (French title: Patapoufs et Filifers). It's a story I read as a child, from the same rather battered copy that my Dad read in his childhood. Out of print for years, it was reissued in 2000 by Jane Nissen Books, translated by Norman Denny. It never occured to me that it was a translation then, but now it is clearly incredibly French!

It tells the story of two boys, one fat and one thin, who find

their way into an underground world divided between two warring nations -

the Fattypuffs and the Thinifers. Whether or not it is intended as an

allegory of Franco-German relations, it has a lot to teach about

tolerance, jingoism, stereotyping and the futility of war - written in 1930, it is clearly informed by the First World War.

Now I know it's still available, I really am going to have to track a copy down - I imagine the copy I remember is long lost, but I will enquire! An abiding childhood memory is of making Fattypuff and Thinifer footprints on the beach by walking on my heels and digging in the edge of a spade. (It was my Dad who started it, so maybe he did that as a child too...) And that's what a good book does - it sticks in your head, gets passed on and creates new worlds, new games.

Mary Schmich's description of reading struck home with me, and it seems especially apt for translated fiction. Here are some of my musings on what I'm reading, re-reading, reading to my children, and translating.

Thursday, 31 May 2012

Wednesday, 30 May 2012

So many questions...

So there we are - all the way from Asterix to Zou. A couple of things I noticed as I was compiling my lists for this blog series set me wondering:

Why do so many translated children's books tackle "difficult" themes (see Brothers, Traitor or The Bear and the Wildcat for example)? And why do a large number of the rest of them seem to be in the fantasy genre?

From my own experience of pitching a translation to publishers it helps if there's some kind of hook, something that makes it stand out from what is already being published in English, so perhaps a different perspective on events, personal experience of war, an unusual topic provides a selling point. But then why aren't books on war, death, illness and so on already on the market? Do UK and US authors just not want to write about them? Or are publishers afraid of them unless they already have a proven track record in another country?

What about fantasy? Where does that come in? There's a particularly strong tradition of fantasy writing in Germany, represented here by Cornelia Funke, and given the Harry Potter phenomenon, perhaps it was just a way of tapping into what was already available to feed the boom. There's also Silverhorse, The Neverending Story and The Book of Time. On the other hand, perhaps I just noticed the fantasy books because it's the sort of thing I liked to read myself as a kid, and still do from time to time.

I don't know - I don't have answers to all these questions. I'd be interested to hear if anyone else has any insight into it though...

Image from FreeDigitalPhotos.net

|

Why do so many translated children's books tackle "difficult" themes (see Brothers, Traitor or The Bear and the Wildcat for example)? And why do a large number of the rest of them seem to be in the fantasy genre?

From my own experience of pitching a translation to publishers it helps if there's some kind of hook, something that makes it stand out from what is already being published in English, so perhaps a different perspective on events, personal experience of war, an unusual topic provides a selling point. But then why aren't books on war, death, illness and so on already on the market? Do UK and US authors just not want to write about them? Or are publishers afraid of them unless they already have a proven track record in another country?

What about fantasy? Where does that come in? There's a particularly strong tradition of fantasy writing in Germany, represented here by Cornelia Funke, and given the Harry Potter phenomenon, perhaps it was just a way of tapping into what was already available to feed the boom. There's also Silverhorse, The Neverending Story and The Book of Time. On the other hand, perhaps I just noticed the fantasy books because it's the sort of thing I liked to read myself as a kid, and still do from time to time.

I don't know - I don't have answers to all these questions. I'd be interested to hear if anyone else has any insight into it though...

Image from FreeDigitalPhotos.net

Tuesday, 29 May 2012

Z is for Zou

Zou is a little zebra created by Michel Gay, a popular French author and illustrator. It's another cracking picture book from Gecko Press, published in 2008.

In a situation parents and small children everywhere will recognise instantly, Zou would like a cuddle in Mummy and Daddy's bed. Unfortunately, Mummy and Daddy just won't wake up, and when they do, they're terribly grumpy. What can he do about this? Then he has an inspiration - coffee! They need lots of coffee...

It's a sweet story, beautifully illustrated (and fortunately it hasn't actually inspired the boys to try and operate the coffee machine or kettle!). Sadly, the translator doesn't seem to be named, but Zou and the Box of Kisses (Gecko Press, 2011) is translated by Linda Burgess. Both boys took to it at once, and it was lovely to hear fils aîné reading it to his little brother on a similar Saturday morning not so long ago.

It was also translated for Clarion Press in the US by Marie Mianowski under the title Zee in 2003, as was Zee is Not Scared (2004).

Here's hoping that Zou à vélo (L'Ecole des Loisirs, 2005) and Les Sous de Zou (L'Ecole des Loisirs, 2011) will also soon be available in English!

In a situation parents and small children everywhere will recognise instantly, Zou would like a cuddle in Mummy and Daddy's bed. Unfortunately, Mummy and Daddy just won't wake up, and when they do, they're terribly grumpy. What can he do about this? Then he has an inspiration - coffee! They need lots of coffee...

It's a sweet story, beautifully illustrated (and fortunately it hasn't actually inspired the boys to try and operate the coffee machine or kettle!). Sadly, the translator doesn't seem to be named, but Zou and the Box of Kisses (Gecko Press, 2011) is translated by Linda Burgess. Both boys took to it at once, and it was lovely to hear fils aîné reading it to his little brother on a similar Saturday morning not so long ago.

"One cup for Mu-u-u-mmy... One cup for Da-a-a-ddy..."

It was also translated for Clarion Press in the US by Marie Mianowski under the title Zee in 2003, as was Zee is Not Scared (2004).

Here's hoping that Zou à vélo (L'Ecole des Loisirs, 2005) and Les Sous de Zou (L'Ecole des Loisirs, 2011) will also soon be available in English!

Labels:

Blogathon 2012,

children's books,

French books,

illustration,

Michel Gay,

picture books,

translation,

zebra,

Zou

Monday, 28 May 2012

Wordle Day

Today is Wordle day on the 2012 Blogathon so here's a word picture of my blog...

You can make your own at www.wordle.net - let me know if you do, I'd love to see it!

Sunday, 27 May 2012

Y is for Kazumi Yamoto

Kazumi Yamoto is a Japanese author and musician. Her books for children and young adults often portray life in an ordinary Japanese home, and also deal with difficult issues like illness and death.

The Friends and Letters from the Living do so for young adults while The Bear and the Wildcat tackles similar themes for younger children.

Originally published in Japan in 2008, Cathy Hirano's elegant translation was published in 2011 by Gecko Press. Their strapline is "Curiously good books from around the world", which seems an excellent goal for a publisher! It also features lovely black and white illustrations by Komako Sakai, one of the most popular illustrators in Japan.

It's a sensitive and touching story of Bear, whose best friend the little

bird has died. For a long time he is inconsolable, but eventually he

ventures out and meets a wildcat who helps him to come to terms with his

loss and face the future. Bear is able to remember the happy times he

shared with the bird.

I've borrowed a copy from the library, and it has come from the bereavement section. Now I've written about it, I'll have to return it as soon as possible, just in case there's anyone out there who needs it.

The Friends and Letters from the Living do so for young adults while The Bear and the Wildcat tackles similar themes for younger children.

Originally published in Japan in 2008, Cathy Hirano's elegant translation was published in 2011 by Gecko Press. Their strapline is "Curiously good books from around the world", which seems an excellent goal for a publisher! It also features lovely black and white illustrations by Komako Sakai, one of the most popular illustrators in Japan.

I've borrowed a copy from the library, and it has come from the bereavement section. Now I've written about it, I'll have to return it as soon as possible, just in case there's anyone out there who needs it.

Saturday, 26 May 2012

X is for Saint-EXupéry

Yes, I know, but it was the best I could do. If you can think of a better topic for X, feel free to let me know in the comments!

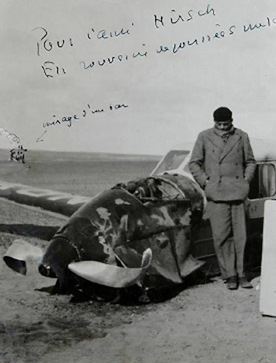

Antoine Marie Jean-Baptiste Roger, comte de Saint Exupéry, to give him his full name, was a pioneering aviator as well as a writer and poet. After a career as a commercial pilot, helping to establish international airmail flights, he joined the French Air Force and later flew for the Free French Air Force despite being officially too old. His last mission was a reconnaissance flight in 1944, in the course of which he is assumed to have been shot down over the Mediterranean - he was never seen again.

He is best-known for The Little Prince (1943), partly inspired by his own experience of a plane crash in 1935. The Little Prince is one of the best-selling books ever written; it has been translated into over 250 languages and dialects and was voted the best book of the twentieth century in France.

So why am I finding it so hard to write about? Partly because it's almost impossible to summarise - an airman crashes in the Sahara Desert, where he meets a Little Prince, a visitor from Asteroid B-612. The Little Prince asks him to draw him a sheep, tells him about his planet and his travels, and they become friends. The airman manages to fix his plane and find water just in time, and the Little Prince leaves after being bitten by a snake. It doesn't sound like much, and completely fails to do the book justice. It's one of those books like Jonathan Livingstone Seagull or The Alchemist that are as much about philosophy as anything else, and which many people find life-affirming, life-changing or whatever, and other people loathe with an equal passion... Added to that, there is the question of whether or not it's even a children's book in the first place. The author says that it is in his dedication, but plenty of people dispute that.

I had a copy as a child, but never read it - what happened to it eventually, I don't know. I later read it in French and completely failed to see what all the fuss was about.

Then, as it happens, two new translations were issued in 2010 - Sarah Ardizzone's translation of Joann Sfar's 2008 graphic novel, published by Walker Books, and Ros and Chloe Schwartz's translation for the Collector's Library. (Oddly, the book jacket spells their surname Schwarz...) The translators of these two versions held gave numerous interviews and discussions about their differing approaches, the challenges of translating such an iconic text and various other related matters, several of which I read. (Here is a clip of Ardizzone and Ros Schwartz on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme.) So, I decided to read both and see if they helped me understand the book better.

I think it's fair to say that they did. And for me, that highlights the importance of translation - even as a translator from French myself, I needed to read this book in my own language to get to grips with what it's all about. And no, I'm not going to try and explain the message - read it for yourself, if you haven't already!

I found the Sfar/Ardizzone version particularly helpful (in which I seem not to be alone - see also here: http://www.graphicnovelreporter.com/content/little-prince-review) as the comic strip format spells out various ambiguities, as well as fleshing out the character of the aviator. Those huge eyes are rather freaky but, like a puppy, they give the Prince a very vulnerable, appealing air.

Both versions concentrate on the sound of the text - the French is very simple and risks sounding clunky in English, so the reason Ros Schwartz worked with her daughter Chloe, was to gain the benefit her musician's ear listening out for duff notes. I particularly like the way they condense un boa ouvert et un boa fermé - "an open boa and a closed boa" - into "elephants inside boa constrictors" or "my two boa constrictors". As all the text in the graphic version is dialogue, Ardizzone had to pay particular attention to making this sound natural. Her "I wish he'd stop bleating on about his sheep!" is particularly inspired.

It's very hard to translate such a well-loved text and, in short, I think both versions have pulled off a great acchievement. I hope that they will be properly appreciated!

Antoine Marie Jean-Baptiste Roger, comte de Saint Exupéry, to give him his full name, was a pioneering aviator as well as a writer and poet. After a career as a commercial pilot, helping to establish international airmail flights, he joined the French Air Force and later flew for the Free French Air Force despite being officially too old. His last mission was a reconnaissance flight in 1944, in the course of which he is assumed to have been shot down over the Mediterranean - he was never seen again.

|

| Saint-Exupéry with the wreckage of his plane in the Sahara |

So why am I finding it so hard to write about? Partly because it's almost impossible to summarise - an airman crashes in the Sahara Desert, where he meets a Little Prince, a visitor from Asteroid B-612. The Little Prince asks him to draw him a sheep, tells him about his planet and his travels, and they become friends. The airman manages to fix his plane and find water just in time, and the Little Prince leaves after being bitten by a snake. It doesn't sound like much, and completely fails to do the book justice. It's one of those books like Jonathan Livingstone Seagull or The Alchemist that are as much about philosophy as anything else, and which many people find life-affirming, life-changing or whatever, and other people loathe with an equal passion... Added to that, there is the question of whether or not it's even a children's book in the first place. The author says that it is in his dedication, but plenty of people dispute that.

I had a copy as a child, but never read it - what happened to it eventually, I don't know. I later read it in French and completely failed to see what all the fuss was about.

I think it's fair to say that they did. And for me, that highlights the importance of translation - even as a translator from French myself, I needed to read this book in my own language to get to grips with what it's all about. And no, I'm not going to try and explain the message - read it for yourself, if you haven't already!

Both versions concentrate on the sound of the text - the French is very simple and risks sounding clunky in English, so the reason Ros Schwartz worked with her daughter Chloe, was to gain the benefit her musician's ear listening out for duff notes. I particularly like the way they condense un boa ouvert et un boa fermé - "an open boa and a closed boa" - into "elephants inside boa constrictors" or "my two boa constrictors". As all the text in the graphic version is dialogue, Ardizzone had to pay particular attention to making this sound natural. Her "I wish he'd stop bleating on about his sheep!" is particularly inspired.

It's very hard to translate such a well-loved text and, in short, I think both versions have pulled off a great acchievement. I hope that they will be properly appreciated!

Friday, 25 May 2012

W is for Weigelt

Udo Weigelt is a German author of picture books who also writes under the name of Moritz Petz.

His picture books include Spring Fever (North-South Books, 2006), illustrated by Sarah Emmanuelle Burg and translated by Marianne Martens, and Fair-Weather Friend (North-South Books, 2003), illustrated by Nora Hilb and translated by J. Alison James.

As you can see, they both feature cats, which is always a good start when it comes to getting our boys interested in them. They're also both quite sweet little stories - Spring Fever is about a tomcat named Freddy, the joys of spring and love in the air. Fair-Weather Friend features a hamster and a cat who are best friends. This doesn't go down too well with the other neighbourhood cats until the gang leader gets into danger and Fritz the hamster saves the day.

Fils cadet has sadly refused point-blank to read either of these so far, and fils aîné was rather more taken with the illustrations than the story, but hey. You can't win them all.

As you can see, they both feature cats, which is always a good start when it comes to getting our boys interested in them. They're also both quite sweet little stories - Spring Fever is about a tomcat named Freddy, the joys of spring and love in the air. Fair-Weather Friend features a hamster and a cat who are best friends. This doesn't go down too well with the other neighbourhood cats until the gang leader gets into danger and Fritz the hamster saves the day.

Fils cadet has sadly refused point-blank to read either of these so far, and fils aîné was rather more taken with the illustrations than the story, but hey. You can't win them all.

Thursday, 24 May 2012

V is for Van Lieshout

|

| Ted van Lieshout |

I was a little confused as to why it was set in the seventies when it was written in the nineties, but apparently it is semi-autobiographical and based on van Lieshout and his own brother (or one of them - he is one of eleven).

I was a little confused as to why it was set in the seventies when it was written in the nineties, but apparently it is semi-autobiographical and based on van Lieshout and his own brother (or one of them - he is one of eleven).It is the story of two brothers, Luke and Marius, yet it begins six months after Marius's death. Their mother wants to burn Marius's things in a grand gesture of farewell. Luke is outraged and determined to save his brother's diary by writing in it himself. So begins a conversation that the brothers could not have had in life. The subtitle of the English translation is Life, Death, Truth and although those are very big themes to be covered in such a slim book, it is a fair reflection of what it is about. Luke discovers the truth of various events in both their lives, beginning to come to terms with his own sexuality and insecurities as he gains an understanding of his brother's. All the while, the question hanging over him is Can you be a brother when your brother is dead?

Being written as a diary, or perhaps a series of letters, it has an immediacy and dry wit that draw the reader in straight away. Occasionally, I found this aspect of the book irritating - it's difficult to give the reader enough background information without breaking character - but for the most part it works. It is moving and sensitive, yet never sentimental, and Lance Salway has succeeded admirably in maintaining that balance in his translation. A word about the title: in Dutch it is Gebr. ("Bros.") yet in English, French, German and Italian (at the very least - those are the languages I understand of the ones I've seen) it has become Brothers. Perhaps this spelling out is inevitable - to me at least Bros. is too reminiscent of the '80s pop group - yet it loses something. As the Nederlands Letterenfonds website points out:

"Van Lieshout uses the abbreviation to indicate a breach in the relationship between two brothers and the premature end of a young life."All the same, even without that little subtlety, it's a poignant and gripping story by a writer unafraid of taking risks and tackling some big ideas. The "scenes of a sexual nature" make it one for older teens, with the publishers pitching it at 15+.

Labels:

Blogathon 2012,

coming of age,

fiction,

gay,

Marsh Award,

reviews,

romance,

teenage,

translation,

young adult

Wednesday, 23 May 2012

U is for the Upside Down Reader...

...by Wilhelm Gruber. A great first chapter book for beginning readers, it's the story of Tim, who learns to read by looking at his sister's school books across the table. Of course this means that he can only read if the book is upside down. Because they think he's too little, his family don't believe that he can read until Grandma comes to stay. Then he surprises everybody by reading the station signs perfectly, but he has to stand on his head first!

Published by NorthSouth Books, the illustrations by Marlies Rieper-Bastian show a German family and a German Bahnhof with the S for the S-Bahn, yet the station names have been changed to Bristol, Salem and Hartford. (From my experience of NorthSouth Books, that might have been an editorial decision rather than one taken by the translator.) The translation by J. Alison James is slightly odd in that it refers to "Mother" and "Dad" - presumably so did the German, but personally I'd have changed it. Otherwise though, it's fine and pitched at just the right level for the target readership. Sadly, once again the author and illustrator gets biogs at the back but not the translator.

Again I had to track down a second-hand copy, but it's worth looking out for if you get a chance. Fils aîné found it very funny and instantly wanted to turn the book upside down to see if he could read it that way too.

Tuesday, 22 May 2012

T is for Traitor...

... my own first published translation.

For my MA dissertation, I chose to write an annotated translation of Die Verräterin by Gudrun Pausewang and I was lucky enough to find a publisher, at Andersen Press, for whom the story resonated with his own experience. Traitor was published in 2004.

It's the story of Anna, a teenage girl living in the Sudetenland at the end of the Second World War. Although this area is now in the Czech Republic, she and her family are German. Anna is fairly ambivalent towards the Nazi regime, but her older brother is fighting in the German army while her younger brother, Felix, is a passionate member of the Hitler Youth. When she meets an escaped Russian prisoner of war, instead of doing her duty and reporting him to the authorities, she helps him - finding him a safe hiding place, bringing him food and clothes. Anna hopes that he will soon escape over the Czech border. As her relationship with Maxim deepens, Anna finds herself questioning more and more about the society around her and becoming much more politically aware.

Pausewang herself lived through this era, in this area, until she and her family were forced to flee from the advancing Russians in 1945. As a girl she was as fanatically pro-Hitler as Felix, yet she became a pacifist and vehemently opposed to war and injustice - her changing views can be seen represented by Anna, her family and friends.

I was particularly keen to translate the book because it presents young readers with a different angle on the Second World War and shows that not all Germans were Nazis. As the fascination with the Third Reich shows no sign of waning, it is good to get this message across. At the same time, negative stereotypes of Germany came about for a reason and I also wanted to challenge any ideas that "This couldn't happen here". Anna's dilemma shows that nobody can ever know how they will react in any given situation. It challenges the reader to wonder what they would have done and flags the importance of individual responsibility. I'm pleased to see from various reader reviews on Amazon, goodreads.com and elsewhere, that other people have responded to the book as I hoped they would.

And, if you'll pardon my blowing my own trumpet a little, who wouldn't be pleased with a review like this?

For my MA dissertation, I chose to write an annotated translation of Die Verräterin by Gudrun Pausewang and I was lucky enough to find a publisher, at Andersen Press, for whom the story resonated with his own experience. Traitor was published in 2004.

It's the story of Anna, a teenage girl living in the Sudetenland at the end of the Second World War. Although this area is now in the Czech Republic, she and her family are German. Anna is fairly ambivalent towards the Nazi regime, but her older brother is fighting in the German army while her younger brother, Felix, is a passionate member of the Hitler Youth. When she meets an escaped Russian prisoner of war, instead of doing her duty and reporting him to the authorities, she helps him - finding him a safe hiding place, bringing him food and clothes. Anna hopes that he will soon escape over the Czech border. As her relationship with Maxim deepens, Anna finds herself questioning more and more about the society around her and becoming much more politically aware.

Pausewang herself lived through this era, in this area, until she and her family were forced to flee from the advancing Russians in 1945. As a girl she was as fanatically pro-Hitler as Felix, yet she became a pacifist and vehemently opposed to war and injustice - her changing views can be seen represented by Anna, her family and friends.

I was particularly keen to translate the book because it presents young readers with a different angle on the Second World War and shows that not all Germans were Nazis. As the fascination with the Third Reich shows no sign of waning, it is good to get this message across. At the same time, negative stereotypes of Germany came about for a reason and I also wanted to challenge any ideas that "This couldn't happen here". Anna's dilemma shows that nobody can ever know how they will react in any given situation. It challenges the reader to wonder what they would have done and flags the importance of individual responsibility. I'm pleased to see from various reader reviews on Amazon, goodreads.com and elsewhere, that other people have responded to the book as I hoped they would.

And, if you'll pardon my blowing my own trumpet a little, who wouldn't be pleased with a review like this?

Monday, 21 May 2012

Haiku Day and Beautiful Blogger Award

I was very flattered to be nominated for a Beautiful Blogger Award by Suzanne at The Tales of Missus P - thank you!

I was very flattered to be nominated for a Beautiful Blogger Award by Suzanne at The Tales of Missus P - thank you!So, this is what happens when you’re nominated:

- You write seven facts about yourself

- You link to the blog of the person who nominated you

- You link to seven bloggers who you think deserve the award

- You let those bloggers know they have been nominated

- I still really, really enjoy colouring in...

- I have spent most of my life in south-east England but...

- I spent three months with a family in the Central African Republic and a year in Saarbrücken, Germany.

- I was an extremely picky eater and now so are my kids - what goes around comes around!

- I grew out of it so, hopefully, so will they...

- I can never pick my favourite book because I have so many.

- I'm not very good at poetry - see below.

Outside, cold and grey:

I open another world -

lost in a good book.

Inspired by that thought, here are seven lovely blogs where we can discover new worlds:

|

| Yes, I'd rather be there than here today! Image: FreeDigitalPhotos.net |

- Lindsay at The Little Reader Library - a really pretty blog and a wide range of interesting reviews.

- Sandra Hume at Little House Travel - a fellow Blogathoner, writing about all things relating to the Little House on the Prairie books by Laura Ingalls Wilder.

- Sarah at Norfolk Bookworm - thoughts of a book blogger local to me.

- Katy Derbyshire at Love German Books - a fellow (but much more prestigious!) German to English translator, based in Berlin - insights into the German book world.

- OK, so it's not book-related, but Venetia is a fellow translator and her Dolcis in Fundo food blog really is beautiful and inspires me to cook!

- Desperate Reader also highlights fascinating books.

- Karen at Euro Crime posts snippets on British and other European crime books, TV and film.

Sunday, 20 May 2012

S is for (Andreas) Steinhöfel...

... a multi-award winning German author and translator. His books Dirk und Ich (My Brother and I) and The Centre of My World have also been translated into English, but the most widely available is The Pasta Detectives, published in 2010 by The Chicken House and translated from the German by Chantal Wright, one of my MA colleagues. It also features new illustrations by Steve Wells. The US edition (2011) is published under the title The Spaghetti Detectives and seems not to be illustrated.

It's the story of Rico, aged 11 and a "child proddity"

This is another book with lots of wordplay as Rico often misunderstands what he hears. He also has difficulty with spelling, so when his teacher encourages him to write a diary the results are interesting, to say the least. As well as managing these challenges adroitly, the translation really catches Rico's voice and his view of the world - his head swirls with ideas like the balls bouncing around in a lottery machine. Some of Rico's ideas are very funny, while others are genuinely thought-provoking. You can see why it was shortlisted for the 2011 Marsh Award for Children's Literature in Translation. The book also won the 2011 NASEN Inclusive Children's Book Award and, with a first person narrator who seems to be somewhere on the austistic spectrum, it has invited comparisons with Mark Haddon's Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time.

There are two more books featuring Rico and Oscar, so let's hope that they will soon also be available in translation so that English-speaking readers can find out what happens next.

It's the story of Rico, aged 11 and a "child proddity"

- "That's a bit like being a child prodigy, but also like the opposite. I think an awful lot, but I need a lot of time to figure things out." -who lives in Berlin with his mum. He has trouble telling the difference between left and right, and gets all kinds of things mixed up, yet he also notices a lot that other people don't see. He becomes friends with Oscar, who is a child prodigy but also prone to anxiety. Together they manage to solve the mystery of what exactly is going on in Rico's building, the "Aldi Kidnapper" or "Mr 2000", and the significance of the "deeper shadows".

This is another book with lots of wordplay as Rico often misunderstands what he hears. He also has difficulty with spelling, so when his teacher encourages him to write a diary the results are interesting, to say the least. As well as managing these challenges adroitly, the translation really catches Rico's voice and his view of the world - his head swirls with ideas like the balls bouncing around in a lottery machine. Some of Rico's ideas are very funny, while others are genuinely thought-provoking. You can see why it was shortlisted for the 2011 Marsh Award for Children's Literature in Translation. The book also won the 2011 NASEN Inclusive Children's Book Award and, with a first person narrator who seems to be somewhere on the austistic spectrum, it has invited comparisons with Mark Haddon's Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time.

There are two more books featuring Rico and Oscar, so let's hope that they will soon also be available in translation so that English-speaking readers can find out what happens next.

Saturday, 19 May 2012

R is for 'The Rainbow Fish'

The Rainbow Fish is the most beautiful fish in the whole ocean but he is so proud and rude that the other fish start avoiding him. Soon he becomes the loneliest fish in the whole ocean and finds himself faced with a choice - will he share his beautiful scales and learn to be happy?

Written by Marcus Pfister, this international best seller, translated from the German by J. Alison James, was published by NorthSouth Books in 1992. The illustrations are bold and striking, with bright colours and shiny foil scales that catch the light. The story is sweetly told, yet almost a parable about the true source of happiness. I rather like the translation, although I've always been puzzled by "happy as a splash" - I don't have a German text to hand for purposes of comparison. Fils aîné is particularly taken with it, even wanting to know why the Rainbow Fish didn't give his very last scale away too, so he could be even happier! There are several other books in the series too - although I haven't read them - which deal with various other childhood issues such as overcoming fears and settling arguments.

Of course, it's always possible for adults to start over-analysing these things - has the rainbow fish truly changed or is he just buying fair-weather friends? What is the role of the mysterious octopus anyway? Isn't it convenient that he knows just the right number of fish to give away all but one of his scales?

Of course, it's always possible for adults to start over-analysing these things - has the rainbow fish truly changed or is he just buying fair-weather friends? What is the role of the mysterious octopus anyway? Isn't it convenient that he knows just the right number of fish to give away all but one of his scales?

I thought I was just messing about with those ideas, but when I glanced at a few reviews on-line, I discovered that the Rainbow Fish is a source of huge controversy. British critics tend to concentrate on the fact that the Rainbow Fish is required to give up his individuality to court acceptance, while certain right-wing Americans are mightily concerned that this evil book is teaching children SOCIALISM! One amazon.com reviewer suggested that the Rainbow Fish should have taught all the other fish how to get their own scales as shiny as his, so that they could all work for success instead of expecting handouts. Meanwhile, according to Neal Boortz, The Rainbow Fish is:

Meanwhile, here's what the author has to say about it:

What do you think? Love it or hate it? A nice message about sharing or Communist propaganda? Let me know!

Written by Marcus Pfister, this international best seller, translated from the German by J. Alison James, was published by NorthSouth Books in 1992. The illustrations are bold and striking, with bright colours and shiny foil scales that catch the light. The story is sweetly told, yet almost a parable about the true source of happiness. I rather like the translation, although I've always been puzzled by "happy as a splash" - I don't have a German text to hand for purposes of comparison. Fils aîné is particularly taken with it, even wanting to know why the Rainbow Fish didn't give his very last scale away too, so he could be even happier! There are several other books in the series too - although I haven't read them - which deal with various other childhood issues such as overcoming fears and settling arguments.

Of course, it's always possible for adults to start over-analysing these things - has the rainbow fish truly changed or is he just buying fair-weather friends? What is the role of the mysterious octopus anyway? Isn't it convenient that he knows just the right number of fish to give away all but one of his scales?

Of course, it's always possible for adults to start over-analysing these things - has the rainbow fish truly changed or is he just buying fair-weather friends? What is the role of the mysterious octopus anyway? Isn't it convenient that he knows just the right number of fish to give away all but one of his scales?I thought I was just messing about with those ideas, but when I glanced at a few reviews on-line, I discovered that the Rainbow Fish is a source of huge controversy. British critics tend to concentrate on the fact that the Rainbow Fish is required to give up his individuality to court acceptance, while certain right-wing Americans are mightily concerned that this evil book is teaching children SOCIALISM! One amazon.com reviewer suggested that the Rainbow Fish should have taught all the other fish how to get their own scales as shiny as his, so that they could all work for success instead of expecting handouts. Meanwhile, according to Neal Boortz, The Rainbow Fish is:

"the most insipid, disgusting and subversive children's book available today."(Which makes me think it must be doing something right...) Here is a rather more balanced critique from Eric Steinman:

"Where this book could easily be teaching honest lessons about the value of communication and sharing, it teaches flawed lessons about being liked and losing yourself to mass popularity." Read more: http://www.care2.com/greenliving/lit-crit-the-rainbow-fish.html#ixzz1vATyotMjand a positive view from Anna M. Ligtenberg:

"The message in this book is more about not letting your possessions possess you, about understanding that others won't like you just because you're pretty, and about recognizing that friendship isn't about someone else adoring you but about sharing something, even if all you share is play time (not necessarily possessions)." Source: http://www.amazon.com/Oh, and if you were wondering whether the debate is due to anything being lost in translation, I can assure you that the reviews on amazon.de are equally polarised.

Meanwhile, here's what the author has to say about it:

"Rainbow Fish has no political message. The story only wants to show us the joy of sharing. We all enjoy making presents for Holidays or birthdays and the warm feeling it gives us when we do so. I want to show children the positive aspect of sharing: To share does not only mean to give away something (what is quite hard for a child), but above all to make someone else happy– and themselves happy by doing it." Source: http://www.marcuspfister.ch/evolution.htmPersonally, I think that most of this fuss comes down to simply reading too much into it. Clearly, Pfister could have made his point in a less clumsy way and avoided such a whirl of controversy, but I also think that children are more likely to understand the book the way it's meant than adults...

What do you think? Love it or hate it? A nice message about sharing or Communist propaganda? Let me know!

Friday, 18 May 2012

Q is for Québec

A guest post by Katy Manck as part of the WordCount Blogathon 2012:

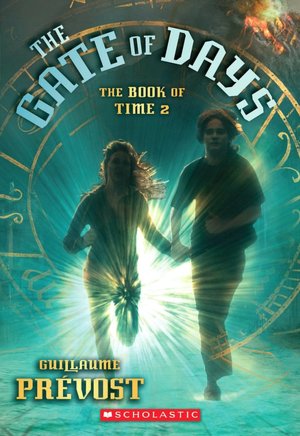

When we first meet Sam in his small Québec hometown in The Book of Time, he’s sure that the junior high bully is going to beat him up. By the end of this compelling young adult trilogy, Sam has become stronger in many ways – as a friend to his cousin Lucy, as a quick thinker and problem solver, as a person who can resist the temptations of easy illegal riches, and as a young man who knows that the perils of going into high school are nothing compared to what he’s faced during his time travels.

When we first meet Sam in his small Québec hometown in The Book of Time, he’s sure that the junior high bully is going to beat him up. By the end of this compelling young adult trilogy, Sam has become stronger in many ways – as a friend to his cousin Lucy, as a quick thinker and problem solver, as a person who can resist the temptations of easy illegal riches, and as a young man who knows that the perils of going into high school are nothing compared to what he’s faced during his time travels.

Series author Guillaume Prévost is a history professor in France and has also written novels for adults – all in French. In a 2007 interview, he stated how much he enjoyed having William Rodarmor translate all three books in The Book of Time series, as Rodarmor frequently consulted him to clarify historical points and plot nuances. When his adult novels were translated, Prévost had very little involvement with the process.

Series author Guillaume Prévost is a history professor in France and has also written novels for adults – all in French. In a 2007 interview, he stated how much he enjoyed having William Rodarmor translate all three books in The Book of Time series, as Rodarmor frequently consulted him to clarify historical points and plot nuances. When his adult novels were translated, Prévost had very little involvement with the process.

As a reader, I feel that having the same translator for the entire series kept the narrative flow clear and the characters’ voices distinct as we hurtled back and forth through Time together. For more details (but no plot spoilers) about the books, please click on each title below to open my recommendation in a new window/tab:

The Book of Time (#1) introduces Sam, his recently bereaved father, and their shared gift of traveling through time using the sunstone and special coins.

The Book of Time (#1) introduces Sam, his recently bereaved father, and their shared gift of traveling through time using the sunstone and special coins.

The Gate of Days (#2) takes Sam and his cousin Lucy to the castle of Vlad Tepes, Chicago’s gangster days, and rumbling Vesuvius as they search for Sam’s dad.

The Circle of Gold (#3) that enables time-travel from any location is what the Archos man seeks, so he holds Sam’s girlfriend hostage in Renaissance Rome until it is found.

Will Sam, his dad, Lucy, and Alicia all get back to Québec safe and sound?

Will the mysterious Archos man be defeated?

You’ll have to read The Book of Time series to find out!

You’ll have to read The Book of Time series to find out!

Check your local library, bookstore, or the publisher:

USA: Arthur A. Levine Books – all 3 books in hardcover

UK: Scholastic Books – first 2 books in paperback

Canada: Scholastic Books – book 1 in paperback

**Katy Manck, MLS

http://BooksYALove.blogspot.com

follow me on Twitter: @BooksYALove

When we first meet Sam in his small Québec hometown in The Book of Time, he’s sure that the junior high bully is going to beat him up. By the end of this compelling young adult trilogy, Sam has become stronger in many ways – as a friend to his cousin Lucy, as a quick thinker and problem solver, as a person who can resist the temptations of easy illegal riches, and as a young man who knows that the perils of going into high school are nothing compared to what he’s faced during his time travels.

When we first meet Sam in his small Québec hometown in The Book of Time, he’s sure that the junior high bully is going to beat him up. By the end of this compelling young adult trilogy, Sam has become stronger in many ways – as a friend to his cousin Lucy, as a quick thinker and problem solver, as a person who can resist the temptations of easy illegal riches, and as a young man who knows that the perils of going into high school are nothing compared to what he’s faced during his time travels. Series author Guillaume Prévost is a history professor in France and has also written novels for adults – all in French. In a 2007 interview, he stated how much he enjoyed having William Rodarmor translate all three books in The Book of Time series, as Rodarmor frequently consulted him to clarify historical points and plot nuances. When his adult novels were translated, Prévost had very little involvement with the process.

Series author Guillaume Prévost is a history professor in France and has also written novels for adults – all in French. In a 2007 interview, he stated how much he enjoyed having William Rodarmor translate all three books in The Book of Time series, as Rodarmor frequently consulted him to clarify historical points and plot nuances. When his adult novels were translated, Prévost had very little involvement with the process.As a reader, I feel that having the same translator for the entire series kept the narrative flow clear and the characters’ voices distinct as we hurtled back and forth through Time together. For more details (but no plot spoilers) about the books, please click on each title below to open my recommendation in a new window/tab:

The Book of Time (#1) introduces Sam, his recently bereaved father, and their shared gift of traveling through time using the sunstone and special coins.

The Book of Time (#1) introduces Sam, his recently bereaved father, and their shared gift of traveling through time using the sunstone and special coins.The Gate of Days (#2) takes Sam and his cousin Lucy to the castle of Vlad Tepes, Chicago’s gangster days, and rumbling Vesuvius as they search for Sam’s dad.

The Circle of Gold (#3) that enables time-travel from any location is what the Archos man seeks, so he holds Sam’s girlfriend hostage in Renaissance Rome until it is found.

Will Sam, his dad, Lucy, and Alicia all get back to Québec safe and sound?

Will the mysterious Archos man be defeated?

You’ll have to read The Book of Time series to find out!

You’ll have to read The Book of Time series to find out! Check your local library, bookstore, or the publisher:

USA: Arthur A. Levine Books – all 3 books in hardcover

UK: Scholastic Books – first 2 books in paperback

Canada: Scholastic Books – book 1 in paperback

**Katy Manck, MLS

http://BooksYALove.blogspot.com

follow me on Twitter: @BooksYALove

About the author: Katy Manck is a retired academic/corporate/school librarian who finds joy in recommending young adult books beyond the bestsellers on her BooksYALove blog. She is treasurer of the International Association of School Librarianship and publicity chair for IASL’s free online international GiggleIT Project for student writers.

Thursday, 17 May 2012

P is for Mrs Pepperpot

"There was an old woman who went to bed at night as old women usually do, and in the morning she woke up as old women usually do. But on this particular morning she found herself shrunk to the size of a pepperpot, and old women don't usually do that. The odd thing was, her name really was Mrs Pepperpot."

|

Mrs Pepperpot's name in Norwegian is Teskjekjerringa, meaning "the teaspoon lady", and she has been around since 1959. Because she never knows when one of her shrinking fits will happen, it can cause all kinds of problems. However, it also enables her to speak to the animals and order the sun and wind around, so she has plenty of adventures as a result. She is also very shrewd about getting things done, whatever her size. The stories are very entertaining whether for reading aloud to young children, or for more confident readers to read themselves, and there is a brisk, fairytale quality to the writing.

(I also find myself wondering whether the creators of Grandpa in my Pocket have been influenced by Mrs Pepperpot... Mind you, Grandpa's shrinking is entirely controlled by the shrinking cap so perhaps not.)

After this little trip down memory lane, I'm feeling quite nostalgic - we really will have to introduce the boys to these stories as soon as possible!

Tuesday, 15 May 2012

O is for Outside In

O is for Outside In:

There is also information on their work bringing international books to children in the UK and a whole range of schemes and events supporting translated children's literature: it really is a worthwhile site to check out!

Meanwhile, here's a range of translated picture books beginning with 'O' that I found there - follow the links below the images to read their reviews:

"the organisation dedicated to promoting and exploring world literature and children's books in translation."I have found this website of enormous help in compiling and researching this A-Z, and the nice people there provide all kinds of ways to discover new books. You can search for a specific author or title, browse by age range or choose a country from an interactive map of the world. Or you can have a look at their book of the week. Not all the books are translations, incidentally - some are written in English by international authors.

There is also information on their work bringing international books to children in the UK and a whole range of schemes and events supporting translated children's literature: it really is a worthwhile site to check out!

Meanwhile, here's a range of translated picture books beginning with 'O' that I found there - follow the links below the images to read their reviews:

|

|

|

|

| Oscar and the Very Hungry Dragon |

N is for 'The Neverending Story'

The Neverending Story by Michael Ende was first published in Germany in 1979 and translated into English by Ralph Manheim in 1983. It is possibly better known for the film released in 1984 - I certainly came to read the book in my teens precisely because I'd enjoyed the film as a child - and yet the film only covers the first half of the book. Apparently, Michael Ende felt that it was so different from what he wrote that he sued the production company when they wouldn't stop production or change its name. He lost.

It is the story of Bastian Balthazar Bux, a boy who runs into a bookshop to escape from bullies. There he discovers a book called 'The Neverending Story' in which the land of Fantastica is under threat from the Nothing, the Childlike Empress is sick and a boy warrior named Atreyu is attempting to find a cure for her illness. As Bastian reads of Atreyu's adventures with Falkor the luckdragon, giants, werewolves and racing snails, he becomes literally drawn into and involved in the book. Eventually he realises that it is up to him to save this world. This is the point where the film finishes, yet Bastian goes on to have further adventures of his own in the world of Fantastica, until he realises that he is in danger of being trapped there forever.

As well as dealing with the importance and power of imagination, and the perils of getting what you wish for, it is about friendship, loyalty and identity. Imagination is not just restricted to the plot, either: each chapter begins with an ornamented initial capital - there are twenty-six of them in alphabetical order - while in some editions, although not the one I read, the text is colour-coded according to whether the action takes place in Fantastica or the real world.

Incidentally, if you'll pardon the digression, David J. Peterson at dedalvs.com invites us to spare a thought for translators working into languages with other script systems. This led me to look into the Japanese translation. I didn't discover how that particular difficulty was overcome, but I learnt that Ende himself was fascinated with Japan and had a huge following there. His second wife was Mariko Sato who translated some of his books into Japanese.

Manheim's translation, meanwhile, deftly follows the German in alternating between a slightly old-fashioned, fairytale manner for the Fantastican parts and a more down-to-earth style. He also clearly had a lot of fun with the names! There were a few minor issues that struck me as odd - in some places the English seemed more extravagant than the German, while on other occasions it was the other way round. All the same, it's well written in either language, and an engrossing read. And if anybody has read it in a non-Latin script, I'd be fascinated to hear how it works!

It is the story of Bastian Balthazar Bux, a boy who runs into a bookshop to escape from bullies. There he discovers a book called 'The Neverending Story' in which the land of Fantastica is under threat from the Nothing, the Childlike Empress is sick and a boy warrior named Atreyu is attempting to find a cure for her illness. As Bastian reads of Atreyu's adventures with Falkor the luckdragon, giants, werewolves and racing snails, he becomes literally drawn into and involved in the book. Eventually he realises that it is up to him to save this world. This is the point where the film finishes, yet Bastian goes on to have further adventures of his own in the world of Fantastica, until he realises that he is in danger of being trapped there forever.

As well as dealing with the importance and power of imagination, and the perils of getting what you wish for, it is about friendship, loyalty and identity. Imagination is not just restricted to the plot, either: each chapter begins with an ornamented initial capital - there are twenty-six of them in alphabetical order - while in some editions, although not the one I read, the text is colour-coded according to whether the action takes place in Fantastica or the real world.

Incidentally, if you'll pardon the digression, David J. Peterson at dedalvs.com invites us to spare a thought for translators working into languages with other script systems. This led me to look into the Japanese translation. I didn't discover how that particular difficulty was overcome, but I learnt that Ende himself was fascinated with Japan and had a huge following there. His second wife was Mariko Sato who translated some of his books into Japanese.

Manheim's translation, meanwhile, deftly follows the German in alternating between a slightly old-fashioned, fairytale manner for the Fantastican parts and a more down-to-earth style. He also clearly had a lot of fun with the names! There were a few minor issues that struck me as odd - in some places the English seemed more extravagant than the German, while on other occasions it was the other way round. All the same, it's well written in either language, and an engrossing read. And if anybody has read it in a non-Latin script, I'd be fascinated to hear how it works!

Monday, 14 May 2012

M is for...

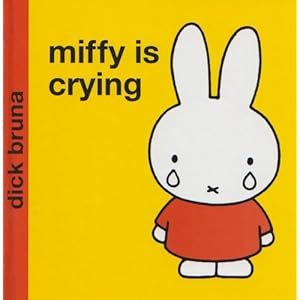

... the Moomins by Tove Jannson, but I was always of the school of thought that found them weird and creepy so I'm not going to write about them. Instead, I'm going to write about Miffy.

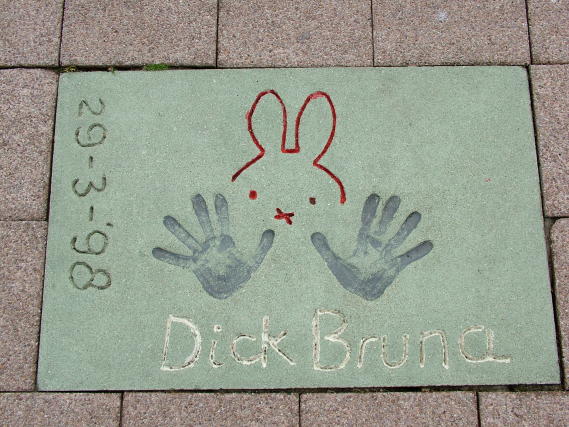

I've had a soft spot for the little white rabbit, created by Dick Bruna over 50 years ago now, since Nijntje became a staple feature of my Dutch lessons at university. Her Dutch name is a shortening of konijntje, meaning "little rabbit". Although each language originally had it's own name for her, it was her first English translator, Olive Jones, who came up with the name Miffy - easily pronouncable around the world - by which she is now known in all languages but Dutch. Later books are translated by Patricia Crampton.

The books are as simple as the illustrations - square format for little hands, bright primary colours, fours lines of rhyming text on each pages - and Miffy has become an international style icon. There's an incredible amount of merchandising out there and she even has her own museum.

Yet despite their simplicity, Bruna manages to convey an incredible amount of emotion in a face made up of two dots and a cross. The early books might be rather dated and un-PC in their gender roles, but the books cover pretty much every aspect of toddlerdom while Miffy at the Gallery (Egmont, 2003) is a lovely introduction to modern art.

|

| Walk of Fame, Rotterdam. Photo by Ziko van Dijk |

I've had a soft spot for the little white rabbit, created by Dick Bruna over 50 years ago now, since Nijntje became a staple feature of my Dutch lessons at university. Her Dutch name is a shortening of konijntje, meaning "little rabbit". Although each language originally had it's own name for her, it was her first English translator, Olive Jones, who came up with the name Miffy - easily pronouncable around the world - by which she is now known in all languages but Dutch. Later books are translated by Patricia Crampton.

The books are as simple as the illustrations - square format for little hands, bright primary colours, fours lines of rhyming text on each pages - and Miffy has become an international style icon. There's an incredible amount of merchandising out there and she even has her own museum.

Yet despite their simplicity, Bruna manages to convey an incredible amount of emotion in a face made up of two dots and a cross. The early books might be rather dated and un-PC in their gender roles, but the books cover pretty much every aspect of toddlerdom while Miffy at the Gallery (Egmont, 2003) is a lovely introduction to modern art.

Labels:

art,

Blogathon 2012,

children's books,

classics,

illustration,

Miffy,

Moomins,

picture books

Sunday, 13 May 2012

L is for Lindgren

|

| German stamp from 2007 showing Astrid Lindgren and Emil |

Astrid Lindgren is apparently the 18th most translated author in the world. Also famous as an active campaigner for children's and animal rights, she wrote over 50 stories including the Emil, Karlson-on-the-Roof, Bill Bergson (Kalle Blomkvist in Swedish) and Bullerby children series. But she's best known for Pippi Longstocking, the strongest nine-year-old girl in the world.

Pippi lives alone (apart from a horse, and a monkey named Mr Nilsson) because her mother died when she was a baby and her father is lost at sea. She is fiercely self-sufficient but becomes good friends with the children next door, Tommi and Annika. Her lack of manners and education have made her contraversial with adults but incredibly popular with children ever since the first publication in 1945. It was felt (and still is, in some quarters) that she encourages rudeness and disrespect. Yet many more people claim Pippi as a role model: a feisty, free-spirited figure showing that there's nothing girls can't do.

Adding to the fun of the Pippi books is the way she plays with language, inventing and mispronouncing words and names, singing nonsense songs, telling jokes and making up riddles. Obviously, this sets her translators a particularly tricky challenge! In the US Pippi Longstocking was translated in 1950 by Florence Lamborn, while it was translated in the UK by Edna Hurup in 1954 and published by Oxford University Press. Meanwhile, Pippi Goes Aboard (1956) and Pippi in the South Seas (1957) were translated by Marianne Turner. For a detailed comparison of these US and UK versions, see here: Pippi Goes Abroad by Madelene Moats.

Adding to the fun of the Pippi books is the way she plays with language, inventing and mispronouncing words and names, singing nonsense songs, telling jokes and making up riddles. Obviously, this sets her translators a particularly tricky challenge! In the US Pippi Longstocking was translated in 1950 by Florence Lamborn, while it was translated in the UK by Edna Hurup in 1954 and published by Oxford University Press. Meanwhile, Pippi Goes Aboard (1956) and Pippi in the South Seas (1957) were translated by Marianne Turner. For a detailed comparison of these US and UK versions, see here: Pippi Goes Abroad by Madelene Moats.Somehow, Pippi Longstocking completely passed me by as a child. Not only did I never read them, I'd never even heard of the books until they began to crop up regularly in discussions of children's literature in translation. So, coming to write about Astrid Lindgren now, I had some catching up to do...

I read the newest translation by Tiina Nunnally (also OUP), published in 2007 and illustrated by Lauren Child of Charlie and Lola fame. Nunnally's translation is described as "sparkling" by the publishers and it certainly reads well. Combined with Child's illustrations it brings a modern air to the book - there are a lot of typographical quirks strongly reminiscent of the Charlie and Lola books. Judging by the examples in the essay I linked to above, it seems closer to the Lamborn translation than the Hurup - perhaps unsurprisingly as Nunnally is also American. She has a deft touch with the word play too - just to use one of the examples quoted by Moats, Pippi makes up a little rhyming ditty as she cooks pancakes for her friends.

I read the newest translation by Tiina Nunnally (also OUP), published in 2007 and illustrated by Lauren Child of Charlie and Lola fame. Nunnally's translation is described as "sparkling" by the publishers and it certainly reads well. Combined with Child's illustrations it brings a modern air to the book - there are a lot of typographical quirks strongly reminiscent of the Charlie and Lola books. Judging by the examples in the essay I linked to above, it seems closer to the Lamborn translation than the Hurup - perhaps unsurprisingly as Nunnally is also American. She has a deft touch with the word play too - just to use one of the examples quoted by Moats, Pippi makes up a little rhyming ditty as she cooks pancakes for her friends.The Swedish text is as follows (the normal word for pancake is pannkaka so an extra syllable has crept in there too):

Nu ska här bakas pannekakas,Hurup's version completely ignores the rhyme and the nonsense:

nu ska här vankas pannekankas,

nu ska här stekas pannekekas. (1945:14)

Here pancakes will be baked now,Lamborn has:

here pancakes will be served now,

here pancakes will be fried now! (1954: 9)

Now we’re going to make a pancake,We can now bring the comparison up to date by adding Nunnally's version:

now there’s going to be a pankee,

now we’re going to fry a pankye. (1977: 20)

Now it's time to make pancakes,To me, the last of these is the punchiest - Lamborn's is OK but doesn't scan so well.

now it's time to flip panclips,

now it's time to shape panchapes! (2007: 20)

From the reviews on Amazon it seems as though this version is succeeding in bringing in new readers attracted by the familiar style of the illustrations, which can only be a good thing. The physical book is also lovely and well produced. My only gripe is that the author and illustrator each get half-page biographies at the back of the book as well as name checks on the back cover and flaps. The translator, who has surely done as much as, if not more than, Lauren Child to make this book work just gets her name on the title page and the aforementioned "sparkling" in the blurb.

Saturday, 12 May 2012

K is for Kaaberbøl

Lene Kaaberbøl to be precise, who is interesting because she translates her own books into English from her native Danish. I don't know of any other instances in children's literature, although I'm sure someone will be able to correct me on that. Self-translation undoubtedly has many advantages - the author/translator knows their own text better than anybody and never has to wonder exactly what some phrase or other means. It also requires a bilingual fluency of a sufficiently high level to be able to write as well in another language as you can in your own - a skill of which I am frankly in awe!

To get a taste of her writing for this A-Z project, I read Kaaberbøl's Silverhorse. The publishers, MacMillan Children's Books, have let this and the sequel Midnight go out of print, which is a shame because it's an excellent book. It is set in a post-apocalyptic world where nobody is allowed to own the land, but it is passed down from mother to daughter. Women are the rulers with a duty to care for the land, and men lead an itinerant life. The main character is 12-year-old Kat, daughter of Tess, the maestra of Crowfoot Inn. Kat has a fiery temper and fights constantly with her stepfather. In the end, Tess has no choice but to send Kat away, despite it being very unusual for a girl to travel in this society. After a disastrous apprenticeship to a dyer, she ends up at the academy for Bredinari, who ride the strange and dangerous hellhorses - wild nightmares crossed with sturdy mountain horses - and serve justice and law in the land of Breda. Here, Kat has to learn to control her temper so she can master the weapons and horses she will need to handle. Events come to a head when she gets caught up in power politics beyond her control or understanding, and finds herself fighting for survival.

To get a taste of her writing for this A-Z project, I read Kaaberbøl's Silverhorse. The publishers, MacMillan Children's Books, have let this and the sequel Midnight go out of print, which is a shame because it's an excellent book. It is set in a post-apocalyptic world where nobody is allowed to own the land, but it is passed down from mother to daughter. Women are the rulers with a duty to care for the land, and men lead an itinerant life. The main character is 12-year-old Kat, daughter of Tess, the maestra of Crowfoot Inn. Kat has a fiery temper and fights constantly with her stepfather. In the end, Tess has no choice but to send Kat away, despite it being very unusual for a girl to travel in this society. After a disastrous apprenticeship to a dyer, she ends up at the academy for Bredinari, who ride the strange and dangerous hellhorses - wild nightmares crossed with sturdy mountain horses - and serve justice and law in the land of Breda. Here, Kat has to learn to control her temper so she can master the weapons and horses she will need to handle. Events come to a head when she gets caught up in power politics beyond her control or understanding, and finds herself fighting for survival.

The plot rattles along at a good pace and Kat is an engaging and sympathetic, if flawed, character. Her struggles with both authority figures and bullies her own age are all too recognisable and the book also tackles the reverse-sexism of her world, snobbery, loyalty, betrayal and true friendship.

I found that as I was reading, I was constantly trying to second-guess Kaaberbøl - had she used this word or that (injust, for example) deliberately for archaic effect or by mistake? - a trap that is all the easier to fall into when the author/translator is known to be writing in a language not her mother tongue. I also found myself irritated by the interjection 'Sweet Our Lady!' - coming from a Christian tradition, I would have found 'Our sweet Lady' or even 'Sweet Lady!' more natural, but then perhaps she was deliberately trying to distance herself from 'Our Lady' as the Virgin Mary... That said, the writing is truly fantastic, in every sense of the word.

Highly recommended!

To get a taste of her writing for this A-Z project, I read Kaaberbøl's Silverhorse. The publishers, MacMillan Children's Books, have let this and the sequel Midnight go out of print, which is a shame because it's an excellent book. It is set in a post-apocalyptic world where nobody is allowed to own the land, but it is passed down from mother to daughter. Women are the rulers with a duty to care for the land, and men lead an itinerant life. The main character is 12-year-old Kat, daughter of Tess, the maestra of Crowfoot Inn. Kat has a fiery temper and fights constantly with her stepfather. In the end, Tess has no choice but to send Kat away, despite it being very unusual for a girl to travel in this society. After a disastrous apprenticeship to a dyer, she ends up at the academy for Bredinari, who ride the strange and dangerous hellhorses - wild nightmares crossed with sturdy mountain horses - and serve justice and law in the land of Breda. Here, Kat has to learn to control her temper so she can master the weapons and horses she will need to handle. Events come to a head when she gets caught up in power politics beyond her control or understanding, and finds herself fighting for survival.

To get a taste of her writing for this A-Z project, I read Kaaberbøl's Silverhorse. The publishers, MacMillan Children's Books, have let this and the sequel Midnight go out of print, which is a shame because it's an excellent book. It is set in a post-apocalyptic world where nobody is allowed to own the land, but it is passed down from mother to daughter. Women are the rulers with a duty to care for the land, and men lead an itinerant life. The main character is 12-year-old Kat, daughter of Tess, the maestra of Crowfoot Inn. Kat has a fiery temper and fights constantly with her stepfather. In the end, Tess has no choice but to send Kat away, despite it being very unusual for a girl to travel in this society. After a disastrous apprenticeship to a dyer, she ends up at the academy for Bredinari, who ride the strange and dangerous hellhorses - wild nightmares crossed with sturdy mountain horses - and serve justice and law in the land of Breda. Here, Kat has to learn to control her temper so she can master the weapons and horses she will need to handle. Events come to a head when she gets caught up in power politics beyond her control or understanding, and finds herself fighting for survival.The plot rattles along at a good pace and Kat is an engaging and sympathetic, if flawed, character. Her struggles with both authority figures and bullies her own age are all too recognisable and the book also tackles the reverse-sexism of her world, snobbery, loyalty, betrayal and true friendship.

I found that as I was reading, I was constantly trying to second-guess Kaaberbøl - had she used this word or that (injust, for example) deliberately for archaic effect or by mistake? - a trap that is all the easier to fall into when the author/translator is known to be writing in a language not her mother tongue. I also found myself irritated by the interjection 'Sweet Our Lady!' - coming from a Christian tradition, I would have found 'Our sweet Lady' or even 'Sweet Lady!' more natural, but then perhaps she was deliberately trying to distance herself from 'Our Lady' as the Virgin Mary... That said, the writing is truly fantastic, in every sense of the word.

Highly recommended!

Friday, 11 May 2012

J is for Joëlle Jolivet and Jean-Luc Fromental...

... both French, he is a highly successful journalist, travel writer and author of novels, children's books and comics; she is an acclaimed designer and illustrator. They have collaborated on several books, including 365 Penguins. Sadly, the translator is uncredited, but the (American) English version was published by Abrams in 2006.

In it, a family receive an unexpected parcel on New Year's Day. It contains a penguin and an anonymous note:

It's Uncle Victor, the ecologist. He's been so worried about the penguins losing their habitat that he decided to resettle them at the North Pole instead. As you can't just export theatened species, he's been sending them one at a time. Now he takes them off in his van, leaving just Chilly as a pet. Things get back to normal until one day a new parcel arrives...

Now, this is an odd one. I want to like it - it's about penguins, and it sneakily teaches kids maths and a lesson about global warming. The illustrations are fun and very expressive. But, but, but, the whole thing sets my inner pedant screaming! What kind of ecologist would come up with such a harebrained and irresponsible plan? Given that the world is heating up, why would the penguins do any better at the North Pole anyway? And that's without even considering the cruelty of sending an animal by post! (Yes, I know. But this stuff bothers me. See this old post here: On Thomas, the Little Red Train etc.)

And another thing, the actual book is enormous. It doesn't fit in the bookcase and it's very hard to hold with a wriggling child on your lap.

On the other hand, the boys love it. Spotting Chilly with his blue feet is an extra game and of course they don't care in the least about the implausibility of it. Hopefully they will also pick up some of the mathsy stuff along the way.

Jolivet and Fromental seem to have made quite an industry out of penguins now and the pop-up book 10 Little Penguins looks charming too. Some pictures of the inside of the German edition can be seen here: fine fine books.

In it, a family receive an unexpected parcel on New Year's Day. It contains a penguin and an anonymous note:

"I'm number 1. Feed me when I'm hungry."The penguins keep coming; they're cute at first but soon start to cause problems. How do you house them, feed them, clean them? And who's sending them? And why?! Along the way, the family find themselves solving various mathematical problems in attempt to calculate their food requirements and storage solutions. By 31 December, their house is full of, you've guessed it, 365 penguins! One of them, named Chilly, has cute little blue feet. While they hold their New Year's Eve party on the lawn the sender of the penguins turns up.

It's Uncle Victor, the ecologist. He's been so worried about the penguins losing their habitat that he decided to resettle them at the North Pole instead. As you can't just export theatened species, he's been sending them one at a time. Now he takes them off in his van, leaving just Chilly as a pet. Things get back to normal until one day a new parcel arrives...

Now, this is an odd one. I want to like it - it's about penguins, and it sneakily teaches kids maths and a lesson about global warming. The illustrations are fun and very expressive. But, but, but, the whole thing sets my inner pedant screaming! What kind of ecologist would come up with such a harebrained and irresponsible plan? Given that the world is heating up, why would the penguins do any better at the North Pole anyway? And that's without even considering the cruelty of sending an animal by post! (Yes, I know. But this stuff bothers me. See this old post here: On Thomas, the Little Red Train etc.)

And another thing, the actual book is enormous. It doesn't fit in the bookcase and it's very hard to hold with a wriggling child on your lap.

On the other hand, the boys love it. Spotting Chilly with his blue feet is an extra game and of course they don't care in the least about the implausibility of it. Hopefully they will also pick up some of the mathsy stuff along the way.

Jolivet and Fromental seem to have made quite an industry out of penguins now and the pop-up book 10 Little Penguins looks charming too. Some pictures of the inside of the German edition can be seen here: fine fine books.

Thursday, 10 May 2012

I is for Isol...

... the author of It's Useful to Have a Duck an unusual and charming accordion-style book that gives you two different viewpoints on the same situation. Originally published in Spanish as Tener un patito es útil, it was translated by Elisa Amado in 2009.

So, what's it about then? Well, a boy finds a duck and uses him, among other things, as a hat, a rocking horse and to clean his ears, before abandoning him in the bath. Quite cute. And then you turn the book over and read the blue pages. Suddenly the book is called It's Useful to Have a Boy. A duck finds a boy and uses him, among other things, as a vantage point on the world, to scratch his back and to polish his bill, before having a swim in the bath and settling down to sleep.

We picked up a second-hand copy recently and both boys took to it straight away. The board book format ought to suggest that it's more suitable for fils cadet (aged 2), but it was fils aînée (aged 5) who was able to appreciate the twist on the blue pages - and highly amusing he found it, too. Definitely recommended, and not just for children!

So, what's it about then? Well, a boy finds a duck and uses him, among other things, as a hat, a rocking horse and to clean his ears, before abandoning him in the bath. Quite cute. And then you turn the book over and read the blue pages. Suddenly the book is called It's Useful to Have a Boy. A duck finds a boy and uses him, among other things, as a vantage point on the world, to scratch his back and to polish his bill, before having a swim in the bath and settling down to sleep.

We picked up a second-hand copy recently and both boys took to it straight away. The board book format ought to suggest that it's more suitable for fils cadet (aged 2), but it was fils aînée (aged 5) who was able to appreciate the twist on the blue pages - and highly amusing he found it, too. Definitely recommended, and not just for children!

Labels:

Blogathon 2012,

board books,

children's books,

ducks,

funny books,

Isol,

recommendations,

reviews,

translation

Wednesday, 9 May 2012

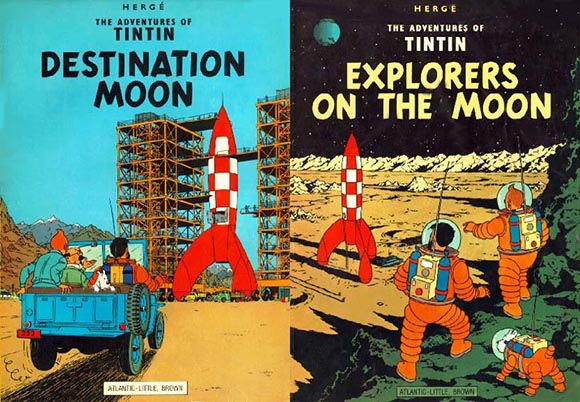

H is for Hergé

Confession time - I was always a very partisan child so, being devoted to Asterix, I never read Tintin. So for today, here's a guest post by my husband and proofreader-in-chief:

H is for Hergé, but really, there’s only one thing anyone thinks of when they hear his name – Tintin.

What’s so great about Tintin? To be honest, that’s a question I’ve asked myself before, since discovering him aged 10 or 11. I loved the books back then, devouring them avidly, and I still have a huge amount of affection for them, but reading Tintin as an adult, it’s hard to pin down exactly where the appeal lies.

The books are certainly of their time – leaving aside some slightly dubious racial attitudes (even apart from the notorious Tintin in the Congo), the modern reader may be surprised to see just how much smoking and heavy drinking there is, something I can’t imagine in more modern books. And in the moon landing stories (Destination Moon, Explorers on the Moon) there’s a jarring reminder that they were written several years before the first launch of the Sputnik Programme, and are closer to Jules Verne and H.G. Wells than modern science fiction.

The characters are drawn with very broad brushes, becoming archetypes if you’re generous, stereotypes if you’re not – the brave young hero, the salty sea-dog and the brilliant but absent-minded professor are all present and correct, while the villains tend to scowl a lot, smoke cigars and regularly use chloroform to abduct people. Maybe this simple characterisation, along with the slightly “boys’ own” style, is what makes it so accessible across cultures.